Thursday, March 31, 2011

The Unmanageable Reading Life

(That sketch courtesy of the brilliant sketch comedy Portlandia.)

Everyone that works in media, the publishing industry, or the arts feels it's their job to consume culture. Some fly by the seat of their pants--following what they know they love, and taking up recommendations once they reach a certain level of mass popularity. (Case-in-point, the flood of Kindle readers who take on bestsellers from previous years once it becomes easy to carry their entire library with them.) Others plan out their year in culture in advance, annotating their calendars with premieres, book parties, and gallery openings. But no matter who you are in this business, inevitably you have to do your homework of following all hot cultural trends. Tools like Twitter and the Approval Matrix, as well as any number of brilliant cultural digests and podcasts, can be invaluable in this respect, but everyone has their own crazy method of staying informed. And when I say these methods can be "crazy", here is what I mean:

My daily reading routine: I click into my Google Reader. What gets read quickly becomes determined by a) what I find entertaining, b) what I find important, and c) what I think should probably be read to stay well-informed. The entertaining posts either get read right away or added to my Instapaper account for later reading, which I can do from my computer or from my iPhone. The important posts get opened and either quickly discarded or scheduled for Tweeting out both for the TK account and my personal account. (A few particularly provocative ones get sent out as posts on Facebook.) The informative posts, if they're news-related and informational in content, get read right away; if they're good for the brain, long thought-provoking pieces, they often fall to the very bottom of my Instapaper account, not to be seen again for several months later. (I have at least three pieces from recent New Yorkers languishing...)

Movie recommendations get thrown onto a Netflix queue. Book recommendations get added to a Goodreads account, then sorted by their publisher, release date, and content. (Novels, non-fiction, and cookbooks all get their own lists.) In my Google documents is a list of forthcoming books I want to review. In a desktop folder on my work computer are at least 20 PDFs and Word docs of books soon-to-be-published that I want to read. Sitting on my desk at home is a stack of books I've committed to reviewing, each with a post-in noting its on-sale date and who the review is for. For those books being read on deadline, the inside cover carries a day-by-day breakdown of how many pages should be read to finish the material on time.

I recently lay out this culture diet for a friend of mine, account by account, commitment by commitment. His response? "That's not a culture diet, that's a culture binge." Of course, he's right. In our information-saturated culture, where anything and everything is available for reading, for perusing, for mulling over late at night, it has become harder and harder to really digest anything. Impressions about great novels become muted when they're read back-to-back; music becomes background noise when it comes secondary to everything else; movies make less of an impact when they're viewed in marathons. (Unless of course these are like Lord of the Rings-extended marathons, in which you come to appreciate both the scope of Tolkein's universe and the benefits of shoes when going on epic quests.) "I don't remember what inspired me anymore," my friend said to me. "I can feel myself getting dumber, and I think I used to remember things better...did we have this problem in the 19th century?"

Of course we didn't. We used to live in a culture where books were more valued objects, where opportunities to consume culture were rarified occurrences, and often the privilege of the elite. (The theater and the opera can still be treated this way, thanks to $100+ tickets.) But with the opening-up of the Internet, a book can be read as a web page, an art gallery can be visited via Google, and new music can be selected based on a single song you already like. With so many new methods to find new entertainment, do we become more cultured? Or do we become more overwhelmed? Is it better to take small bites of art, or huge mouthfuls?

I don't have an answer to this question yet, but if you found a great article, and asked me today, "Did you read it?" I probably did. Whether I remember anything about it is the real conundrum.

Wednesday, March 23, 2011

Limited

As it happens, I saw it with a colleague. I should’ve been writing my launch presentation for the next day, but he suggested the movie, and I, never one to pass up a mediocre sci-fi flick, agreed. “All I know about it,” he revealed ominously, “is that this is the number one movie in the country.” “Oh, no.”

The movie’s conceit, you probably know, plays off the medical myth (debunked—kind of—at Snopes) that we use only a small percentage of our brainpower. In the movie, Bradley Cooper stumbles on a miracle drug that allows him to “access all of [his] brain.” Whatever that actually means, in the world of the movie it turns him into a total freakin’ rockstar from Mars.

“Let’s just hope,” my friend fondly hoped, “he doesn’t work in publishing.”

Prescienter words are rarely spoken. Bradley Cooper plays a writer who is late delivering his manuscript. He is dumped by his editor girlfriend (no, she’s not his editor, there just happen to be lots of editors in this movie), played by the terrible Abbie Cornish; at the movie’s beginning, she’s just been promoted: “I have my own assistant!” she gloats.

When he scores NZT (the drug’s name eerily recalls a certain “male enhancement” pill), Cooper’s character finishes his book in a four-day writing binge that looks a lot like a coke spree but less sweaty. And on the fifth day, he plops his manuscript on his stunned editor’s desk. “Just read the first three pages,” he says. “If you don’t like it, I’ll return my advance.” He may be an Übermensch, but his agent would never let him talk like that.

The bulk of the movie takes place in the couple weeks after Cooper’s character improbably delivers his book. Then he takes his superbrains and goes into mergers and acquisitions. (Wouldn’t you?)

Toward the end of the film, we skip providentially ahead Twelve Months Later: foregrounded in the scene, but forgotten by the plot of the movie, is a finished copy of the novel. It appears as if by magic, attended by total irrelevance. Which is, to be fair, probably how these things seem to happen in the real world.

Thursday, March 17, 2011

The Touch of a Woman

In the twenty years since she graduated from Stanford, Einhorn has amassed a formidable résumé that should inspire even the most forlorn editorial assistant; she began at FSG and rose all the way up to Editor-in-Chief at Hachette behemoth Grand Central Publishing. However, a few years ago Penguin approached her with an offer that I don’t think anyone could refuse—that of her own imprint. She moved to 375 Hudson Street in 2007, and launched Amy Einhorn Books in 2009.

And what a launch it was: The Help was one of the imprint’s first titles, boasting a simply intertwined lower-case “a” and “e” logo on its spine. It must have been a hard act to follow, but several of Einhorn’s more recent books, such as The Postmistress and The Weird Sisters, have also hit the list (though admittedly not with the soaring staying power of The Help).

With its record of stunning success, Amy Einhorn Books is firmly established as an imprint. In fact, I think Amy Einhorn Books is more accurately described as a brand, in that the presence of its logo seems to function as a Good Housekeeping Seal for readers—last year, a group of bloggers kicked off the “Amy Einhorn Perpetual Reading Challenge” on Twitter, encouraging people to read their way through the entire catalog. Although a mix of fiction and nonfiction, her titles share common sensibilities despite their varying subjects, and readers seem to have picked up on this identifiable aesthetic.

Amy Einhorn Books, however, is far from the first eponymous boutique imprint to be helmed by a female editor. Nan A. Talese Books (Doubleday), Reagan Arthur Books (Little, Brown), and Sarah Crichton Books (FSG) are some of its most recognizable predecessors, all founded by women who are venerated in publishing circles for their charisma and talent. I don’t think you’d have to throw a stone too far to hit a young editrix with a small “woman-crush” on, say, Reagan (ahem).

It’s interesting to consider the brand power of these imprints alongside their function within the larger context of their parent house/imprint. Once upon a time, there was a Nelson Doubleday; a Roger Straus, a John Farrar, and a Robert Giroux; an Alfred A. Knopf; a Charles Scribner; a Charles Coffin Little and a James Brown. One can easily forget that the imprints bearing these names were once small ventures, too, each defined by the personality and editorial taste of their founders. But will their trajectory of growth and power be followed by this new school of lady imprints? In fifty years, will we be referring just to “Talese” and “Arthur”? Will “Einhorn” in its turn be a maternal umbrella for other smaller imprints?

Equally worthy of discussion is whether or not there will space in the industry for my publishing generation to produce its own personality-driven imprints in twenty years’ time. Despite the success of Einhorn and Arthur, there is also a trend now towards more concept-oriented imprints, like Twelve and the short-lived HarperStudio. Are ideas, rather than people, now the bigger draw?

What also intrigues me is that both of these imprints were started by men. Given that the industry’s biggest houses and imprints are named after men, is it now considered un-politically correct by the industry for a younger generation of male editors to found new imprints boasting their names? Or does this difference stem from the common theory that women read more books, especially more fiction, than do men, and therefore that a name-brand imprint led by a woman has more influence in the marketplace?

I raise all these questions not to provide rhetorical flourishes, but because I honestly can’t answer them. I don’t think anyone really can. I just hope that Amy and Reagan and Nan and Sarah continue to rock on, and allow their taste to sing out loudly in this crowded bookstore of a world.

Wednesday, March 16, 2011

A Childhood Bookshelf Revealed

This is probably the oldest book in my room. My dad, ever the ambitious English professor, gave this to me when I was…8? 9? Whatever the age, it was surely too early to encounter the unexpurgated text of the Grimm tales. The 242 stories herein are bloody as hell and tremendously anti-Semitic. And I read each story at least 4 or 5 times. I was…a pretty confused child. But now I have a keen eye for folk tale tropes!

Sophomore year of high school. My classmates and I were just starting to read real books in French class. Recall how insufferable 15-year-olds are. Now imagine a classroom of 15-year-olds reading Sartre in French. Yeah, I thought I was worldly as shit. The only reason this book looks so tattered is that I likely toted it around in my bag for months after completing it, so I could whip it out while waiting for my mom to check out at Stop n Shop and look so deep.

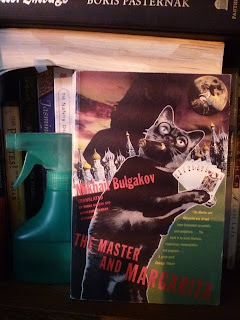

The most formative and weird period of my young adulthood was my four-month-long study abroad term in Glasgow during my junior year of college. My classmates and I were enrolled in English literature courses at the University of Glasgow, and I opted to have my one elective course be yet another literature course instead of something fun, like studio art or Scotch distilling. In short, my study abroad experience was more monk-like than spring break. Glasgow in the fall gets about 5 hours of daylight daily, most of which I spent in the library reading Jacobean revenge dramas and strange books like The Master and Margarita. Among the essay deadlines for my three lit classes, I barely found the time to feed myself, letting myself believe that my roommate’s orange Bacardi Breeze was an acceptable substitute for orange juice at breakfast time. This cracked-out British jacket for The Master and Margarita is a fitting illustration of how my life felt at that time. Best four months of my life!

This book is a stand-in for an intense graphic novel phase I went through senior year of college—coincidentally, the same year that my college introduced a course on graphic novels. We read so many Pantheon titles…and then I graduated, moved to New York City, got a job at Random House, and started working on those titles! DREAMS REALLY DO COME TRUE.

So. Have I come any closer to answering my post’s question? I’m not sure. I suspect I should have read more age-appropriate books. But what I’m really interested in are the books haunting your childhood shelves. Do it up in the comments!

Monday, March 14, 2011

Does alcohol breed good writing habits?

Say what you will about the quality of my writing (I know, I know, as many sentences as not are run-ons, and I totally overuse parentheses, I sometimes can’t resist going a little un-artfully sentimental, and I’ve never been published outside of this blog), but about the quantity of my writing I feel pretty good. I write one line poems on subway cars headed back to Brooklyn after long days at the office, I have notebooks filled with novel openings, and I’ve got several blog posts lined up and waiting to be polished. When I started taking writing workshops again about a year ago I promised myself to never workshop the same story twice, and so far I’ve been able to stick to that.

No, I’m not bragging. I don’t think I’m a particularly inspired writer, or that I suffer writer’s block any less than any other aspirants. The key is that the very moment a good (or, let’s be honest, even decent) idea—be it for a blog post, a short story, an opening line of an as yet-to-be-determined project, or even a screenplay I have no aspirations to write—comes to me, I immediately pick up the nearest pen and closest piece of paper and scribble away. Sometimes this commitment requires ducking into small bodegas to buy an overpriced pen that usually doesn’t last very long even though I have an entire drawer of pens at home. On more than one occasion the only available paper has been a cocktail napkin or the margins of an already published book. My boyfriend Ben (the biggest Michigan football fan around) and I made a big to-do about watching last year’s opening game out at a bar. A tribute at half time inspired a short story idea that I spent the second half of the game filling cocktail napkins with until, line by line, the story was finished. Thursday nights are pretty sacred for Ben and me—we watch NBC’s sitcom line-up (The Office, 30 Rock, etc) over a beer or two and generally unwind after a long week. But when the idea for the Alice Munro/Grey’s Anatomy post that I wrote a few weeks ago hit me while he was on a quick beer run in between shows I still put the whole thing down, word for word. (He’s known me long enough that when he came home to see me scribbling furiously all I had to say was, “I thought of a blog post” for him to retreat gamely to the other side of the couch to wait for me to finish—he’s the best, that one.)

This habit wasn’t born out of discipline, determination, or even a willing time commitment to my hobby. They key to doing this is being aware of the fact that the ideas that come to all of us suddenly, at odd times throughout the day, are not going to stick around forever. (How many times have all of us though, “huh, that’s not a bad idea, remember that for later,” only to never give it a second thought?) After all, if you’ve forgotten you had a good idea in the first place, you don’t realize there’s a problem. You’ve forgotten that there was anything to be lost. You’ve forgotten that there’s anything that was worth saving that wasn’t saved.

And here’s where the alcohol comes in. The channel through which I first realized how well fleeting thoughts can serve a writer in the end was the not small amount of alcohol I drank in college, as undergrads are wont to do. As many of you well know, alcohol—and more particularly having drunken quite a lot of it with masses of close friends in the midst of all kinds of seemingly compelling drama that the young love to breed—makes even the most cynical a bit whimsical, sentimental, or poetic. As an English major, I used to drunkenly text myself the one liners and notes that were inspired by the things and people I saw when I was out on Saturday nights far past when I should have been. The next mornings I would always wake a little stunned to see that I had over a dozen or so texts, and was always both relived and a little bit embarrassed to see that they were all from me to me, and all scraps of drunken creativity.

After engaging in this horribly embarrassing quirk enough times, I realized that, in the midst of the sea of ridiculous senselessness and jumble of horribly misspelled words that resulted, there were actually a few gems worth saving and building a piece for one of my workshops from. Once this became apparent, I started saving all the random ideas I had for the pieces I was working on, whether they came to me in a fraternity lodge at two o’clock in the morning or in the corner of the library at four in the afternoon. I had seen first hand that a line or a thought or an observation pulled from thin air could eventually become something much fuller, and after seeing that proven true enough times, was more than game to cultivate the scraps that came to me, even if some of them (okay, most of them) amounted to nothing. Thus, the habit I outlined at the start of this post—writing down every little thought, essentially—was born.

Perhaps this alcohol-spawned pattern offers some small insight into why so many of the writers that dot the literature landscape’s past were total boozehounds. Maybe the flashes of brilliance that inspired their great works came to them in the middle of a shin digs of Gastsby-esque proportions, or after a wine fueled dinner with the one who would eventually get away. Maybe they only captured those flashes of brilliance that would eventually be fleshed out into staples of freshmen lit classes for years to come because they felt sentimental enough, there in the glow of a candlelit bar room, or under the intoxicating lull of champagne bubbles, to write it down and cherish it. Maybe if those ideas had first come to them in the middle of a meeting with an accountant, or at a lunch with their boss at an average nine to five gig, the details of the every day and the demands they make on all of us would have made the more practical portions of their brains that were currently being engaged convince them to put away their fanciful aspirations, at least for the moment? Maybe writers don’t happen to have a fondness for a glass or two of the fermented, maybe they became writers because said glasses kept them up, engaged in activities worth writing about and compelled to do so?

Thursday, March 10, 2011

Corrections from the Assisterati

Oh, dear...this, again?

The New York Observer has published an article on assistants in the publishing world. That's assistants to editors, agents, scouts, and publicists (never mind those assistants in design, production, and on the financial side), the group of which the article’s author, Kat Stoeffel, has deigned to call "The Assisterati." Judging from the industry responses--and the responses of the assistants around me--Stoeffel has gotten quite a few things wrong in this article. So let's take them to task:

1) Where they come from: Of a gathering of the Assisterati, Stoeffel says, "most of the guests were already connected through a network of private colleges on the East Coast . . . Some were on intimate terms, having attended the same summer camp, the Columbia Publishing Course." Certainly yes, a handful of publishing assistants emerge from excellent colleges and universities on the East coast. And some of them attended intensive summer programs like the NYU Publishing Institute, the Columbia Publishing Course, and other such immersive workshops that cram a lifetime of publishing experience (and an extraordinary series of panels headed by industry leaders) into a brief six weeks. (It's not much of a summer camp, more like a graduate-school-level boot camp.) But Stoeffel makes this all seem serendipitous, a product of privilege rather than deliberate planning for a deeply desired career. First, the geographic and economic spread among entry-level publishing employees is fairly large: I've worked with assistants who studied on the West Coast, the Midwest, the Deep South, the EU, in India, and in South Africa, and all of them had widely varying levels of economic support by way of hard-earned loans and scholarships. Secondly, the choice to attend summer publishing programs is hardly made just to gain cultural cache. While these programs carry a price tag (about $7000 for CPC, $5000 for NYU), they represent a fraction of the price and time that a person would need to commit for a master's degree in English or Journalism (usually upwards of $25,000). And because they are focused on the questions and concerns surrounding the publishing industry, they provide a unique advantage for people that are deeply committed to having a long career learning its nuances of the industry. (Remember that phrase, "deeply committed" in mind.)

2) Who do they think they are? Stoeffel starts to go into the character and attitudes of the Assisterati: "They are the caretakers, soon to be inheritors, of a sublime patrimony. Their proximity to literary creation . . . suggests they possess a cultural credibility they couldn't acquire in, say, Chicago, or on Wall Street. Underpaid but brimming with hope, they, like the people they assist, will one day run this town and steer the course of American literature." If you care about what you do, if you believe what you're doing has worth, you will take a great deal of pride in it. I freely confess that, because I work in an industry that values intelligent voices and finds ways to promote them in the public cultural sphere, I think what I do has an intrinsic value and it gives me cultural credibility. People who work in publishing are part of a tradition (which is vastly different than a patrimony) of finding ways to disseminate great thoughts by great writers, and if that's what Stoeffel wants to call arrogant, then fine, we're arrogant. (And so are all the folks in the denigrated Chicago or Wall Street communities she mentions, since I'm sure they often take as much pride in their work as we do in ours.) And as far as her pithy remarks regarding the attitudes of assistants across different departments, it seems the antipathy she perceives comes from the pettiest of interviewees. When the assistants in our office gather every Friday for a glass of wine and an hour of laughs, it doesn’t matter whether their author is a Twitter phenomenon or a poet of critical acclaim, or if they wear the elegant heels of a publicist or the papercuts of an editor. They all earned the right to be there for a drink, to celebrate the tremendous work and dedication they do every day.

3) Why they ended up getting hired, and what they actually do: Stoeffel says that, while the Assisterati may have lofty dreams of controlling the literary world, their cultural cache is rarely put to work. “Once they settle into their cubicles, these traits are about as valuable as perfect punctuation in the cover letter of a slush submission.” She goes on to quote assistants who are daunted by administrative tasks and secretarial work such as arranging travel plans, mailing packages, and Xeroxing manuscripts. Most egregiously, she suggests that many assistants continue to do these tasks as the only method of harmoniously bonding with their bosses, who serve as “gatekeepers to the kind of meaningful work—acquiring or editing books—that they must master in order to move up the ladder.” Yes, any entry-level assistant will have some level of administrative work to do, and unless they’ve worked in an office setting before, some of it will be new to them. (I’ve often wished that colleges would create seminars for graduating seniors called “Office Etiquette and Paperwork 101,” just so you could learn the multitudes of UPS and FedEx mailing options before your first interviews.) But every office environment requires this. Until publishing becomes an all-electronic industry (god forbid), someone has to mail galleys and xerox manuscripts, circulate jackets and turn over the foul copy. These are all steps in how a house functions from day to day, and demonstrate what it means to be entry-level: to see the work from the ground-floor up. And the bond with the boss is not just about sucking up or playing a “shell game,” it’s also sometimes about having a true mentor-protégée relationship that can benefit both participants. I can show my boss how I learn about breaking media news by way of Facebook, Twitter, and my Google Reader; she can fill me in on meetings regarding developments in the e-book world and new acquisitions. The difference between the Mad-Men-esque secretarial role that Stoeffel imagines, and the reality of the symbiotic relationship between established editor and aspiring assistant, couldn’t be more stark. Stoeffel is writing from a perspective that says apprenticeship and grunt work doesn’t matter—strange, given that she seems to have skipped into her Observer position by way of three internships (the majority of which are unpaid and entirely made of grunt work). Curiouser and curiouser…

4) The ones that stick around: Stoeffel notes that many assistants harbor other dreams—of writing, of traveling, of becoming pastry chefs—and some eventually leave to pursue those dreams. This is hardly news—every profession experiences some turnover. But who Stoeffel forgets to address—the population she leaves out entirely—are the many, many assistants whose dreams are to become champions of great writers through deliberate scouting around the world, dedicated representation of an author’s potential, nuanced editing of an important text, and spirited publicity of a great finished product. Those who figure out that this business isn’t for them will often leave early, and we wish them well. But for those of us who are deeply committed to this business, to this process—the making of books—it’s deeply offensive to see our dedication branded as naiveté. For those of us that threw ourselves into high school and college English courses, edited our local papers and magazines, took on unpaid internships while waiting tables, and now spend nights and weekends reading manuscripts and magazines and attending literary events, this was anything but a light, romanticized career choice. And when a reporter writes a glib, poorly researched, and intentionally inflammatory article just to get the media community talking about how offended they are, it’s more than just a raspberry being blown our way. The Observer is not meant to be Stoeffel’s personal LiveJournal on which to snark and speculate and insinuate that other people are wasting their time. If anything, her article was a profound waste of our time. We, after all, have real work to do.

Monday, March 7, 2011

Publishing Movie Myths Debunked!

The Wonder Boys

In this touching and very funny Michael Chabon adaptation Robert Downey Jr. plays Terry Crabtree, an editor who makes a sojourn to Pittsburg to visit Professor Grady Tripp (Michael Douglas), his star writer who is struggling to finish his second novel. (His first was met with a cascade of acclaim and put Terry Crabtree on the map as an editor.) Though discovering one great writer can indeed launch the career up-and-coming editor, that well-played acquisition usually leads to others. Being in a position to acquire is the key (as opposed to finding anything worth acquiring), and once you’ve jumped through all the hoops in front of you to acquire your first masterpiece the process usually tends to become easier. If Crabtree was hungry enough to sign Tripp up, it feels unlikely that he wouldn’t have found other manuscripts to further build his list. His being desperate enough to make a house call to a writer felt like a bit of stretch. That said, the sophomore slump can, sadly, be very real for successful debut novelists, and the movie gets the snarky writing workshop environment spot on!

Postgrad

The most obvious weakness in this light and fun rom com starring The Gilmore Girls’s Alexis Bledel is the premise that there’s a thriving book publishing industry in Los Angeles. Determined to take the publishing world by storm, Bledel’s Ryden Malby starts the movie thrilled that she has an interview with an editor at Hepperman and Browining, “the best publishing house in all of LA.” My “Um, what? There’s more than one?” was quickly followed by, “Wait, there’s even one?” That said, the details of a young assistant’s life are pretty accurate (we do tend to keep late hours, and manuscript reading is usually done on your own time unless you’re in the middle of a blissfully slow period), but in true Hollywood fashion, the diva-ish ways of those we report to are embellished more than a bit. (No, I’ve never had to scrape gum of the bottom of any editor’s shoe. Most editors keep all personal favors—even the humane ones—to a minimum.) Probably the most spot on is the detail that Ryden gets the coveted job months after she applied for it. The publishing world is so small that often times if an editor likes a resume or candidate who’s not quite right for the job in question they’ll save him or her on file for future openings, or pass them along to friends. Often times the job offer call comes when you least expect it. Sadly also true in that vein is the scene in which Ryden waits for her interview in a room full of other qualified and eager candidates. There are more aspiring editors than there are jobs!

Labor Pains

This movie also had the questionable premise of a publishing house based in LA, but because of all of the other details of the film that seem to be inspired by a magical world far far away from this one, it was less noticeable. This one pretty much gets everything wrong—publishing, human nature, comedic timing. In the weak plot, Lindsay Lohan invents a pregnancy to prevent her three headed monster of a boss from firing her from her editorial assistant job. I’m pretty sure it’s not illegal to fire a pregnant woman (especially one as inept at her job as Lohan’s character seems to be), just horribly villainous and heartless, which the boss in question certainly is. The other thing that sets this one apart from all the others that had at least a modicum of truth imbedded in their tales is that in every other movie here there was whiff of the glamour in the fledgling publishing careers on display. Sure, the protagonists worked long hours and struggled with the rigid hierarchy, but there was the sense that they were pursuing a dream that made the pitfalls worth it, not slumming it. Here the office feels a little bit like a desert version of the one featured on Steve Carell’s The Office, filled with unambitious nine-to-fivers who find most of their joy outside the work place. While not everybody in publishing is a beauty queen, the homeliness of Lohan’s co-workers and their simple, shoddy wardrobes seemed to be an intentional part of the plot, as if it was one of the defining characteristics of the business. While there’s a smiley acceptance of just about any clothing style in our offices (one of my favorite details of the work environment here) the vast majority of the office doesn’t find their wardrobe at vintage seventies thrift stores. Given that this is a Lindsay Lohan movie that went straight to video, none of this should be terribly surprising. The only real mysteries here are how they got so many real comedians to co-star (everyone from Creed from The Office to Janeane Garofalo has a bit part or cameo), and more importantly, how Amazon found people to give the DVD rave reviews. Seriously, check out the Amazon page and see how they glow! Really, America?

The Proposal

The office views found in this one are familiar (our offices, too, have walls of windows that look out on the Manhattan skyline), the author and publisher names they toss around like confetti are legit (with the exception of the imprint that über-editor Sandra Bullock and her assistant Ryan Reynolds work for), and yes, it really is THAT big of a deal to land Oprah. Less accurate is the power Sandra Bullock’s character holds over the entire floor, controlling and ruining lives en masse. While some big name bosses can demand a lot of personal attention and sacrifices from their employees, there’s no one person that everyone reports to directly. (And it must be said, some bosses are a dream to work for—I never once saw a super supportive mentor boss in any of these films, and they do exist!) No, Ryan Reynolds’s character is not too old to still be an assistant. There are very few jumps to make along the publishing ladder, even over an entire career (editorial assistant, associate editor, editor, senior editor), so you’re at each one for awhile. Also, the bigger the name you work for (or the more powerful the editor) the longer it makes sense to work for him or her. Despite the absurd (but hilarious) premise and Bullock’s wild twist as villain, the details ring pretty true.

The Last Days of Disco

It’s a bit tricky to evaluate this one for accuracy as a publishing novice in 2011, given that it’s set in the publishing world of the seventies. Perhaps a more interesting question than what is accurate about this and what is made up is what from that now antiquated world has remained in our current one. Believe it or not the typewriters that line the sets of this movie are still typing strong along senior editor row in 2011. It’s only recently that some of our legendary veterans and path pavers have made the switch from typewriters to computers. While crafting a reader’s report is no longer as communal an effort as it seems to be in the film, the dream of all young assistants seems not to have wavered from then to now: an associate editor gig is what we’re after. Perhaps most interesting is that in the movie—which came out years before the James Frey scandal—the protagonist’s dream book that she is finally able to sign up turns out to be fraudulent. The author made it all up and presented it as fact. Looks like the non-fiction Pinocchio problem that rears its head in a major way every few years is a tale as old as time. Despite the publishing details and their veracity or lack thereof, this is a fabulous film that I’d recommend to just about anyone, not just those interested or invested in the business.

Suburban Girl

This one is based on a handful of stories from Melissa Banks’s collection The Good Girl’s Guide to Hunting and Fishing, which is one of my favorite books about publishing, or just about anything, really. The opening scene, in which the young associate editor protagonist named Brett Eisenberg (yes, named after that Brett, and played by Sarah Michelle Gellar) moves copies of her latest book to the front of her neighborhood book store didn’t ring quite true only because book placement is a detail managed by the marketing and sales departments as opposed to editors. The only other slight veer off course was a scene at a book party, in which the rude and legendarily literary host pushes the young Brett aside to speak to her older and more established suitor. Though it’s not uncommon to be the youngest person by about twenty years at the book parties we assistants attend, I find that the older and more established writers and editors are rather embracing. (I’ll never forget when Gay Talese approached me at a book party just to find out how things are going in the publishing industry these days, and what it’s like to be a young person in the trenches.) Seeing a younger set nervously clutching a champagne flute in the corner reminds them of their early days, I imagine. Some of my best conversations and contacts have been made at parties just like the one featured in that scene, and with people just as large in stature as the famous host. The rest of the film, though, is filled with deliciously spot on touches—everything from the copyediting marks that Brett scribbles across her manuscript pages to that magical moment when you see someone reading a book you’ve spent the last year working on; the reality of reader’s report insecurity and second guessing your opinion, and the conviction that at the end of the day you just have to trust your gut. Small touches like mentions of real life legends like agent Binky Urban also went a long way. Perhaps most notably, though, the movie is quite lovely in its capturing of the nostalgia that permeates our industry. Those who have been in this business for years love to talk about the legendary moments that dot its past—encounters with larger-than-life and infamous writers now long gone; the discovery of a book that went on to change the canon—almost as much as those of us just starting out love to hear them.

Thursday, March 3, 2011

Schmoozing and Boozing

In his Townies column today for The New York Times, writer and former editor at Harper's Magazine Theodore Ross delves into the rituals of the office cocktail, and how alcohol acts like a lubricant when it comes to talking shop, and making books. "The past few weeks the better part of my social life has revolved around drinks," he says, as he looks back on his last days in the office. "Publishing tends to liberally grease the runners of those it transports out the door." He's not wrong: whenever someone departs our offices, we often salute them with Dixie cups full of champagne, and then follow them out of the office with a happy hour nearby. But the tradition applies beyond farewells: Fridays at Five, chats with agents and authors outside the office, schmoozing at book parties and literary events. After a while, you start to feel like an extra on "Mad Men," even if you don't have a bar cart of mixers in your office.

Of course, this trend in the literary world is also famously destructive. Dozens of history's most brilliant writers, editors, and agents have been documented as alcoholics and party people. When you look back at their names--John Cheever, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Dorothy Parker, and so on--it's impossible to separate their reputations as artists from their reputations as drinkers. Some say it's the process of creation that makes them hit the bottle--after writing his masterpiece In Cold Blood, many said Truman Capote was so devastated by what he'd experienced in his bond with the executed murderer Perry Smith that it drove him to drink, and he was never the same after that. One has to wonder if it was the mood of the time to drink and socialize--the cocktail parties of the Paris Review back in the day were infamously debaucherous--or if it was the condition of creation. Is it an indispensable part of the life of the written word, to soak oneself with a bottle of gin?

But I don't mean to get too down on your social lubricant of choice--because alcohol does have one very good impact on the writerly experience: for those that can hold it and not fall asleep too quickly, it has a great reputation for making writers bolder, speaking their minds. (This was parodied to hilarious effect on a recent episode of Glee, in which the club's main diva readied herself with a glass of rose as she prepared to call someone to ask them out--the idea being, if she experienced more heartbreak, she'd have something worth writing songs about.) I'd heard multitudes of writing student friends talk about throwing back a martini before sitting down to write, to quiet the editorial voices in their head. Yes, this is psychosomatic drinking, but it can have real-world benefits every now and then. At the literary event I attended last night, the booze made sense: it was a Q&A at Powerhouse Books with Gabrielle Hamilton, the brilliant chef from Prune who has just written her memoir, Blood, Bones & Butter. I devoured a rough copy of the manuscript several weeks ago, and haven't been able to stop raving about it since. As I sat in this Q&A, listening to this funny, humble, beautifully unpretentious woman talk about her career in cooking, I sipped a complimentary cup of wine and felt emboldened to contribute to the discussion. The wine did much more than taste good, it may me brave enough to talk to a writer who had inspired and moved me through her work. If there's something to blame on the alcohol, I'm glad it was the chance to participate in a conversation about how we make books that make us better. And then we go home and throw back a few in anticipation of the work ahead...